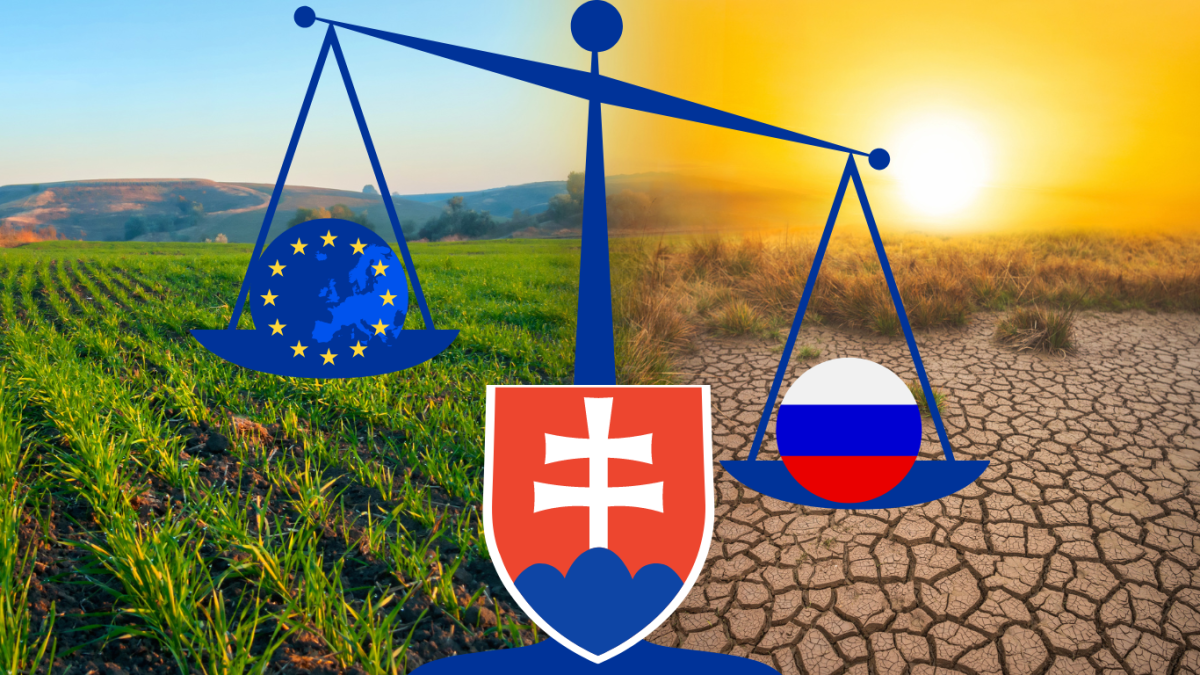

Slovak Government Targets NGOs with Proposed “Foreign Agents Act”

Published: Mar 21, 2024 Reading time: 3 minutes Share: Share an articleAs an organisation with roots steeped in the freedom and civic movements of post-Cold-War Czechoslovakia, we are appalled to see the illiberal turn taken by the Slovak government. The Fico government's proposal to impose a Russian-style foreign agents' law is anathema to the shared goals of the Czech and Slovak people who fought to end the Russian subjugation of our homelands. This is of great concern and sadness to us at People in Need.

As humanitarians, and human rights defenders, we know from over three decades of experience that civil society plays a vital role in the promotion of democracy, transparency and accountability within their countries. We also know that NGOs are an added value to the countries in which they work. Often, civil society—be it through societal movements, civil society organisations, or non-governmental organisations like ours—take up the slack that the state cannot, especially in certain social services and emergency situations. To brand organisations that seek to help the least fortunate or those critical of harmful state policies is an act of self-harm by the state.

The Slovakian government's proposed measures to curb critical media and NGOs, which would mirror tactics employed by autocrats and dictators in places ranging from Russia to Latin America, have raised concerns about the erosion of civil liberties and the stifling of dissent. In a move reminiscent of authoritarian regimes, officials seek to designate these entities as "foreign agents," a term often utilised to suppress opposition voices.

The Fico government has already taken steps to cut NGO funding, raising further alarms about the independence of civil society activities. Additionally, Culture Minister Martina Šimkovičová and Justice Minister Boris Susko have initiated cuts to subsidy programmes, redirecting funds away from NGOs to other areas, citing concerns about transparency and favouritism in grant allocation. The government's actions have prompted backlash from NGOs, with 90 organisations signing a petition against the minister's decisions.

Drawing on our own experiences operating in regions governed by authoritarian rule, we recognise such actions as deliberate attempts to undermine civil society. Branding NGOs, CSOs and human rights watchdogs as agents of foreign influence is a tool of autocratic regimes, typically accompanied by restrictions on free speech, assembly, and other fundamental liberties.

Though proponents draw the comparison between Slovakia's proposal and the US Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA) of 1938, the comparison is little more than an attempt to legitimise a measure condemned by liberal democracies. While FARA primarily targets entities directly controlled by foreign governments, the Slovak initiative is broader, encompassing non-profit organisations engaged in various vitally important social and civic activities.

Critics highlight that similar blacklisting strategies are commonly employed in authoritarian regimes such as Venezuela and Kyrgyzstan and often brutally so in places like Russia and Nicaragua. In these nations, NGOs advocating for human rights, government accountability, and historical truth have faced accusations of treason, subjecting them to oppressive restrictions and state-sponsored harassment.

In Russia, organisations like Transparency International, Golos (an election monitoring group), and Memorial (a research institute focusing on Soviet-era repression) have found themselves labelled "foreign agents." And faced subsequent repression. This designation impedes operations and tarnishes reputations, forcing them to navigate a hostile regulatory environment or shut down entirely.

The proposed measures in Slovakia reflect a concerning trend towards authoritarian tactics, potentially undermining democratic principles and strongly discouraging dissent. Despite government claims of redirecting funds to support vulnerable groups, NGOs fear that these moves could threaten their activities and Slovakia's broader civil society landscape, drawing comparisons to past periods of government pressure during the era of "normalisation" in the 1970s and 1980s. As the country contemplates joining the ranks of authoritarian nations employing these tactics, concerns over the erosion of civil liberties and the suppression of free speech loom large.